To operate reliably, the US electrical grid needs to balance supply and demand: to make sure, at any given moment, that the amount of electricity demanded by homes, businesses, and factories is equal to the amount being supplied by nuclear reactors, gas turbines, and other types of power plants.

energy

The startup emerged from stealth with a goal of extending the range of EVs while also eliminating fossil fuels from home heating.

Demand for gas power-generation hardware is surging, but the few companies that make it are reluctant to scale up.

New York's skyscrapers soar above a century-old steam network that still warms the city. While the rest of the world moved to hot water, Manhattanites still buy steam by the megapound.

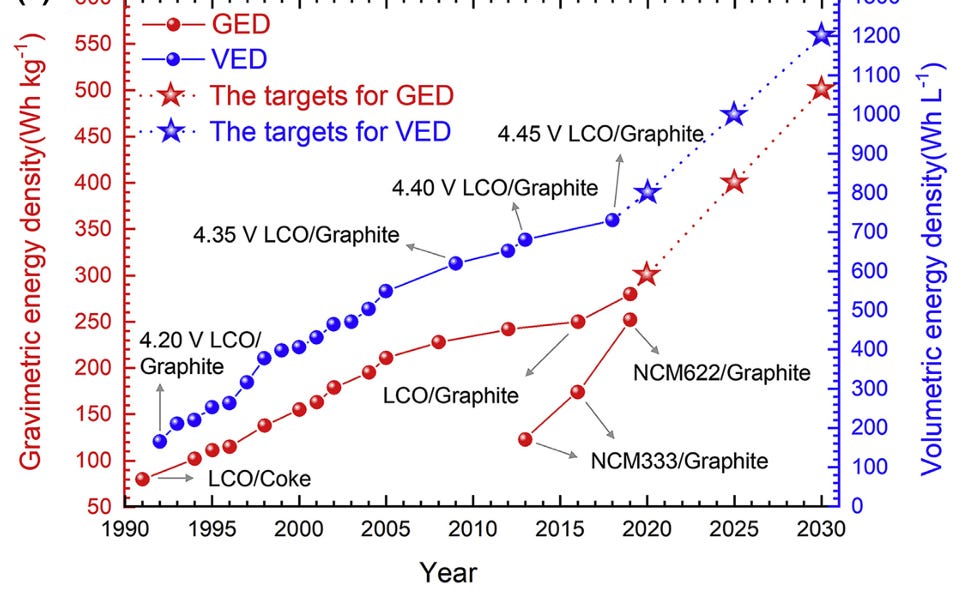

It took decades of research, performed around the world, before a practical lithium-ion battery was possible.

Several of the initial development partners balk at the terms of a federal tax credit that places restrictions on the amount of carbon in the hydrogen production process.

[Note that this article is a transcript of the video embedded above.] This is not smoke. And this isn’t a smoke stack (at least not the kind we normally think of). It serves a totally different purpose at a power plant than smoke stacks whose job is moving combustion products high into the air, al

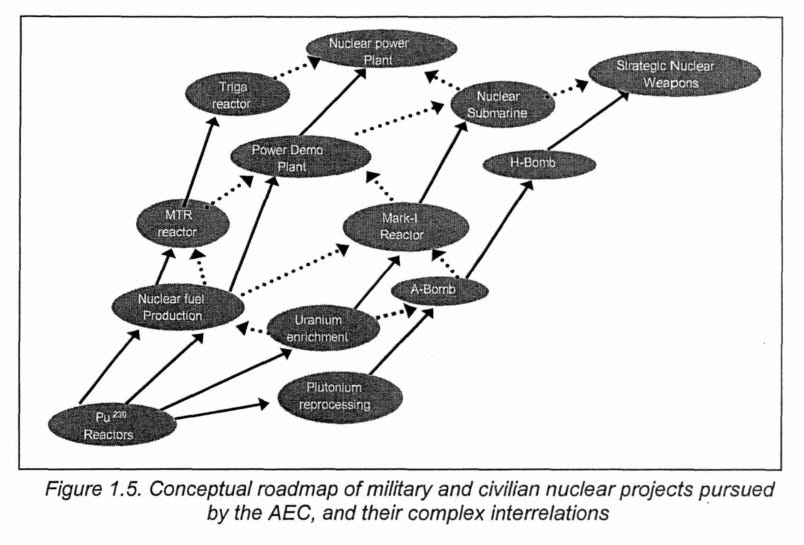

AI takes a lot of power. Why did we stop it again? Today's deeper dive on Nuclear power and why I think it will power AI in the future.

The ATLAS facility will use three ultra-high intensity lasers to initiate the same reaction that powers the Sun and stars.

One of the oldest, scarcest elements in the universe has given us treatments for mental illness, ovenproof casserole dishes and electric cars. But how much do we really know about lithium?

With gains in solar and wind, 22 percent of the nation's electricity comes from renewables, bringing the country closer to its climate goals.

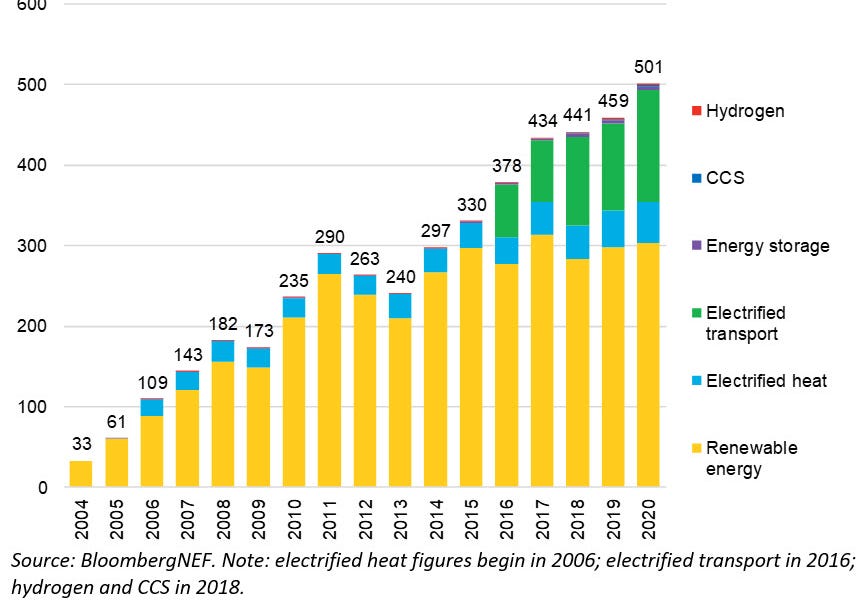

In the first quarter of this year, private investors poured 40% more money into clean energy and electric vehicles than they did in Q1 2023.

Output hit a record last year, and producers expect a future where coal will be required to balance renewable energy for decades.

A novel technique called Underground Gravity Energy Storage turns decommissioned mines into long-term energy storage solutions, thereby supporting the sustainable energy transition.

Ethanol is a comically inefficient form of solar energy—and a toxic one. Putting regular solar panels on some of that land would be better.

Investors have historically been skeptical of green hydrogen. High production costs, expensive infrastructure builds, competition with batteries and

Mining and processing the minerals needed to meet the growing demand for EVs can be costly for workers, local communities and the environment.

A new prototype compatible with a wide range of materials could grab a continuous supply of renewable energy from the air.

Tesla speculated electricity from thin air was possible – now the question is whether it will be possible to harness it on the scale needed to power our homes

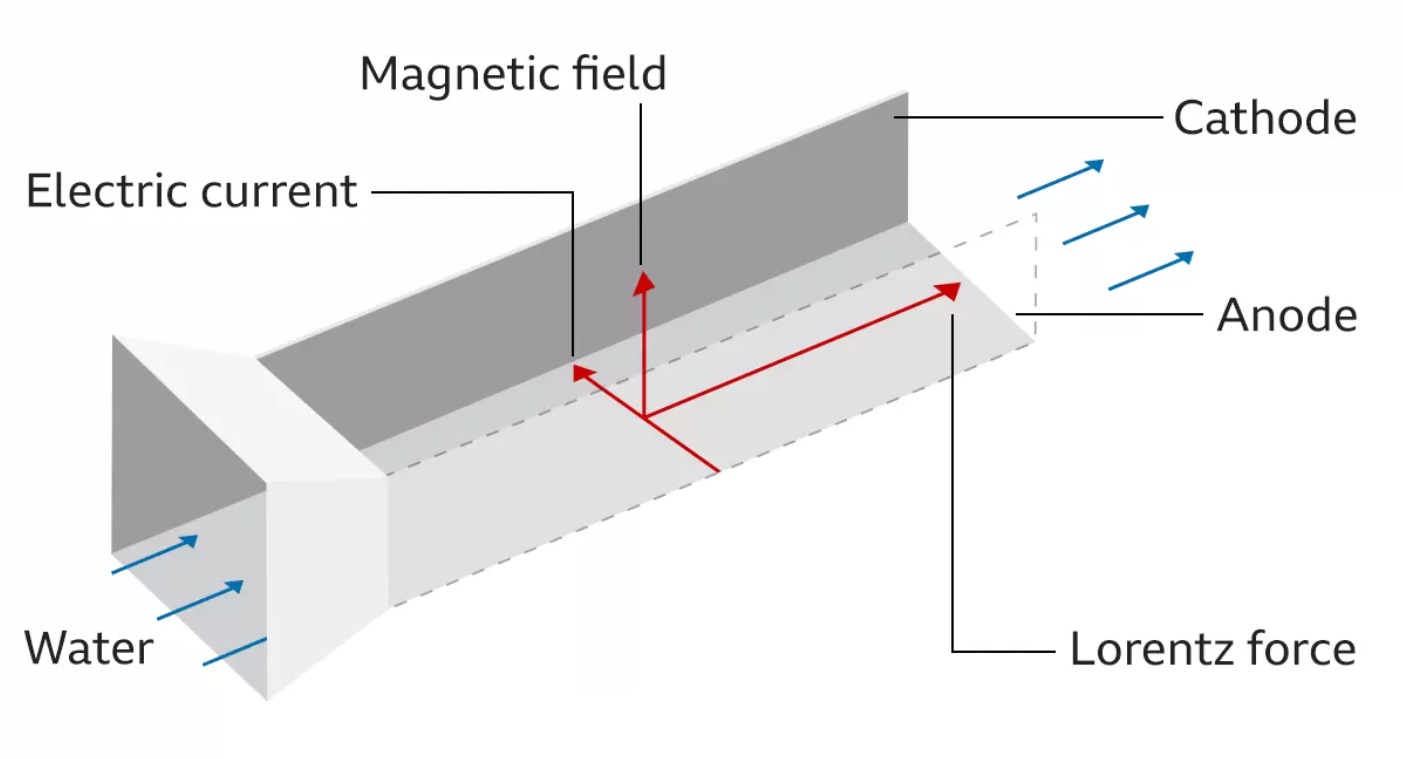

DARPA, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is now working on developing a magnet-driven silent water propulsion system - the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) drive. The primary reason is to develop silent military naval craft. Imagine a nuclear submarine with an MHD drive, without moving parts, that can slice through the water silently. No moving parts

“In one week [in March], we sold more nuclear power plant contracts than any company in all of history,” says @LastEnergy CEO Bret Kugelmass.

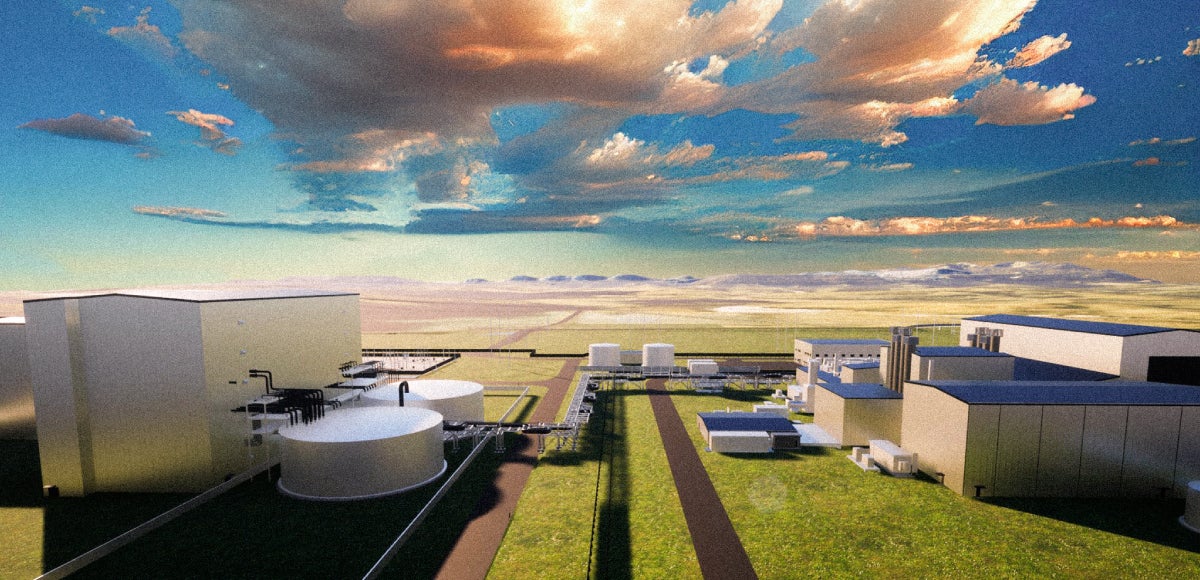

Bill Gates writes about visiting Kemmerer, Wyoming, the future site of the fourth-generation Natrium nuclear power plant being designed by TerraPower.

Energy storage – both home-scale and utility-scale – has become more relevant as the use of renewable energy for electricity generation proliferates. It is particularly topical recently, as the Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits specifically targeting energy storage projects. Energy storage (chemical batteries, pumped hydro storage, gravity-based batteries) transports electrical energy through time, from generation earlier to consumption later. Storage works when the aggregate amount of energy generated is adequate to satisfy aggregate demand, but there is a mismatch in the timing of supply and demand. Some basic fact patterns are: Demand More Variable than Supply. As discussed in previous posts, there is both a daily and a seasonal cycle to electricity usage. If a region’s generation is dominated by traditional base-load type power plants with high and constant generation capacity (nuclear, coal) or are quickly dispatchable (natural gas), there are two basic choices for meeting demand: either have enough generation capacity to cover the peak usage at any time, or marry sub-peak generation with the ability to store energy when demand is below supply and then release it for use when demand exceeds capacity. Supply More Variable through time than Demand. Supply can also be more variable than demand. Solar, for instance, generates electricity only during an 8-14 hour period during the daytime. The daily cycle of electricity usage varies but not this much: there is meaningful demand in the evening and through the night. So a grid with significant solar power will likely need to store daytime-generated energy to be deployed at night. Unplanned Intermittancy. A special case of supply variability: power outages due to storms or maintenance, or unfavorable weather conditions for solar / wind, can cause generation to temporarily fall short of demand. This post will illustrate, using real-world electricity demand data and overly simplistic supply models (with no unplanned outages or weather intermittency) what profile of storage could be useful: how much energy capacity is needed and how frequently it is used. In all cases there will be a real-world question of whether it is more efficient to deploy capital in storage solutions or more generation capacity to compensate. A complete answer to that question is beyond the scope of this post, but my analysis provides some indication of feasibility of different architectures. Here’s a summary: In the constant generation model of traditional generation plants, it appears feasible to use battery storage to substitute for power generation that would cover the last ~10 - 20% of peak demand. Somewhat frustratingly, the strong variability of demand still means that this implies generation capacity that is adequate to supply more than 1.5 times the aggregate energy needs. In a variable generation model like predominantly solar,1 there is some benefit in warm climates with mild winters from aligning higher summer generation with higher summer demand. But substantial storage is needed (probably more than is economical) to manage the day-night cycle. As with fixed generation however, there is so much variability of demand over time that the generation capacity measured in GWh needs to be a reasonable multiple of aggregate energy consumed. A combination, heavily weighted towards fixed, can get benefits of both fixed generation (no daily cycle) and solar (more generation with higher summer demand). This post ignores wind power, which is too unpredictable for me to handle at this time. ↩

The decision would allow an enormous $8 billion drilling project in the largest expanse of pristine wilderness in the United States.

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fpocket-syndicated-images.s3.amazonaws.com%2Farticles%2F8171%2F1662665423_631a42256d12f.png)

It’d be much cheaper than lithium battery storage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/50/9950548a-eff6-4f99-bfb2-77fc401eed62/julaug2022_e04_prologue.jpg)

Back in the 19th century, coal was the nation's newfangled fuel source—and it faced the same resistance as wind and solar today

Plus: Hydrogen pipelines, Advanced Market Commitments, and what made solar energy cheap

Despite repeated claims that the prospects for commercialization have never looked brighter, the stark reality is that practical fusion-based electric power remains a very distant prospect.

Engineers at MIT and NREL have developed a heat engine with no moving parts that is as efficient as a steam turbine.

Doing the right thing makes other right things happen

Finding green energy when the winds are calm and the skies are cloudy has been a challenge. Storing it in giant concrete blocks could be the answer.

Forget ‘peak oil’. Nafeez Ahmed reveals how the oil and gas industries are cannibalising themselves as the costs of fossil fuel extraction mount

Even scientists who were skeptical of work at the National Ignition Facility called the results a success.

So far, most large investments in energy storage have gone to companies building lithium-ion batteries. SoftBank's newest bet changes that.

King Coal is being dethroned, and faster than forecast.

It's not a trick question: You can make a battery out of concrete by storing gravitational potential energy.

Declining costs have helped some of the country's smallest electricity providers expand their use of solar in highly innovative ways

An “operating system” for power could double the efficiency of the grid.