Americans can’t get enough of its favorite macronutrient. Big Food is heeding the call.

Americans can’t get enough of its favorite macronutrient. Big Food is heeding the call.

Japanese utopians. Corporate glow-ups. $400 smoothies. The strange history of the world’s most cultish grocery store.

Could you build a company like Publix today?

American food supplies are increasingly channeled through a handful of big companies: Amazon, Walmart, FreshDirect, Blue Apron. What do we lose when local supermarkets go under? A lot -- and Kevin Kelley wants to stop that.

The future of grocery shopping might just be a 100-year-old grocery chain with a cult following.

Behind the bubbly cashiers in Hawaiian shirts, craveable snacks, and bargain-basement prices are questionable business practices that have many food brands crying foul at the company’s blatant and aggressive copycat culture.

Inflation has changed the way many Americans shop. Now, those changes in consumer habits are helping bring down inflation.

The grocer created a cult brand with sales of $16B+ a year by doing the opposite of industry best-practices (from wages to product to ads).

In a former Toys “R” Us, you can buy Nepali dumplings, get your eyebrows threaded, and pick up merguez sausages.

When it comes to buying food, sight has usurped all other senses. What are the consequences of relegating smell, taste, and touch to the sidelines?

A bunch of razor-thin restaurant margins doesn’t make a fortune so much as a bed of razors.

Kroger is following in the footsteps of Giant Eagle, attempting to phase out its print inserts in newspapers and mailed to homes in favor of digital alternatives.

More than 70 proposed dollar stores have been rejected since 2019, a report shows. It’s a small number compared with those that opened but evidence of opposition to the industry.

When you use supermarket discount cards, you are sharing much more than what is in your cart—and grocery chains like Kroger are reaping huge profits selling this data to brands and advertisers

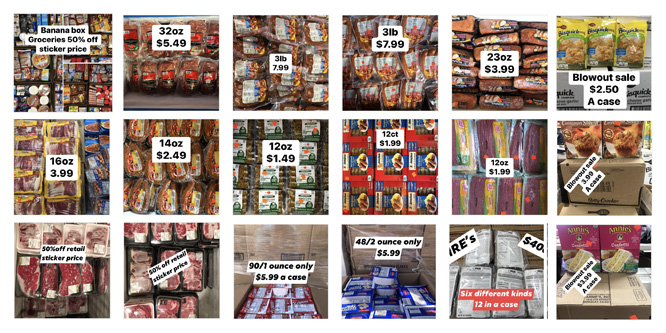

In an inflationary era when customers are increasingly strapped for cash and hunting for discounts, a category of ultra-low-priced grocers that sell the unsellable is growing in popularity. Do you expect mainstream grocers to change their protocols for "unsellable" CPG items if inflation persists?

Store brands are shrouded in secrecy. Who makes them?

A grocer in Utah is opening a store that aspires to focus on meal prep instead of just selling groceries, guiding customers to cook creatively with a limited number of locally produced ingredients. Will a grocer with a stripped-down inventory, dedicated to helping customers with meal prep, succeed in the long run?

Some shoppers find joy in daily trips to the grocery store simply for the community, let alone the miracle of abundance.

We live in a world shaped by shopping carts. The ubiquitous, unloved contraptions are a key feature of US economy. (Yes, really.)

Instacart crunches petabytes daily to predict what will be on grocery shelves and even how long it will take to find parking

Apoorva Mehta’s grocery delivery app is now an essential—and booming—business. Now the 34-year-old billionaire has to show he can outfox Bezos, dodge an avalanche of new competitors and calm his rebellious workers and restless partners.

These days my Instagram feed feels more like QVC than a social network. And many of these companies are enjoying tremendous success pitching natural deodorants, unique underwear, creative candles, glam glasses, stunning shoes -- all manner of well-crafted microbrands. We’re witnessing a cambrian explosion of new consumer startups.

The U.S. grocery industry has reached an uncertain crossroads, facing competition from many sources, but especially German discount stores ALDI and LIDL, who are aggressively expanding across the United States. Whether U.S. retailers will maintain their market share hinges on how they use private-label products (also called white-label goods or store brands) to fight back. In France, grocers were able to repel ALDI and LIDL by offering private-label goods that were both affordable and high quality, but in the UK, retailers chose to offer super-budget private-label items. They might have been cheap, but they were very low-quality, and consumers punished them. The U.S. doesn’t have a lot of experience with private-label goods, so American retailers will have to come up to speed quickly if they hope to maintain their advantage.

Supermarkets have always played tricks on your mind. Can they help you to eat better?